Restoration

DISCOVERY, DESTRUCTION AND RESTORATION

The size and scope of the garden was radically enlarged when in 2007 the site adjacent to the south side of the known garden, was stripped out in preparation for a hostile housing development, during which a large stretch of what was to be called the Tudor Wall was demolished. Over13 metres of a sparkling C16th flint wall enlivened with brick diamonds was demolished thanks to complacency by the Medway Council and the incompetence of the appointed archaeologist. In a frantic attempt to save the remaining section we contacted English Heritage who spot listed Grade II the remains of the wall. Simultaneously we mounted a campaign and launched a petition, which attracted 9000 signatures.

The council acceded to the need for further archaeology and during July 2008 extensive remains of a significant historic garden were uncovered.

SAVING THE GARDEN

Early in 2008, with the demolition of the Tudor Wall, we had tried to buy the garden site, which comprised about 20% by value of the hostile development, but our offer was scornfully rejected. However in August of 2008 the recession struck and Future Homes went into administration almost overnight. We again tried to buy the garden site but the administrators were obliged to sell the development as a whole. We explored this possibility and finally offered the same £1.25 million, which we were told, would be rejected.

However in our fight to save the Tudor Garden we had taken Medway Council to the High Court where a Judicial Review found that the council had failed to consult English Heritage nor obtained Listed Building Consent for this part of the development, our argument relying on the judgment that the Tudor garden was part of the curtilage of Vines House, itself listed Grade 2*. The court ruling in our favour meant there was now a question as to the legality of the planning permission as well as heritage obstacles to the obtaining of a new one. These obstacles progressively deterred other bidders and ours was the only offer where these legalities worked in our favour. Finally in December 2009 our offer was accepted.

Lower ragstone courses of East walls.

Western terrace.

Unearthed arches in plinth of North wall.

Steps to High Terrace.

RECREATING THE GARDEN –TUDOR OR MANNERIST? 2010-PRESENT

Further archaeology and the demolition of the houses confirmed the presence of a major garden, with 3 levels, and terraces on three sides with walks up to 15’ wide. However modern carports and access roads encroached on two of those terraces and the Tudor wall was groaning under the weight of these interventions. There has been a long history of abuse of the site, knowingly and unknowingly, with all the neighbouring freeholds variously exploiting its vulnerability and decrying its heritage status and our conviction.

Scrupulous attention to the archaeology and the incorporation of all the remains became our way forward as the detailed presence of more walls and staircases, their materials and construction methods emerged. Initially our only aim was to copy like for like, but gradually many questions were raised, opportunities seen, where no original answer was in the offing. Indeed it seemed increasingly likely that there were 2 or more early phases of the garden’s development, one perhaps around 1540 (after the dissolution of the monastery at Rochester cathedral), the other between 1600 and 1640. This latter was when Restoration House was being aggrandized with its Mannerist façade. This period under Henry Clerke was one of prosperity and preferment, the Recorder of Rochester becoming its MP in 1621, 1625, 1626, Reader Middle Temple 1629, Serjeant at Law 1631, Treasurer Serjeant’s Inn Chancery Lane 1642-4 and in receipt of numerous perquisites. An ambitious garden upgrade, utilizing the fashionable Italian influence of Inigo Jones was the order of the day. Just as Jones’ masques roamed stylistically through Roman, medieval and Renaissance styles, so it became clearer to us that the recreation of the garden would be enlivened with flourishes of imagination where no literal evidence survived.

Where evidence did survive it had a Renaissance flavour. The terrace in front of the brick and flint Tudor wall was of red brick (English bond) and with a subtle backward batter to its face. Additionally it featured concealed buttresses to the rear, a characteristic of Renaissance defensive building to prevent enemies scaling the face. This naked slanting brick face corresponds with the plinth like ground floor of a renaissance palazzo, with the extravagant and vertical brick and flint diaper wall corresponding to an elaborately fenestrated piano nobile (first floor), while the High Terrace above corresponds with the attic, thus creating a Renaissance form and conforming for example with the front of the Pitti Palace in Florence, which with its attendant Boboli gardens was well known in England.

Into this elevation we inserted water cannons shooting into turreted rills punctuating the plinth floor. On top of this wall a series of upright pipes form an arcade of water railings, while a semi spherical opening in the centre, encircles a statue splashing with more canon fire. This so called Chalice acts as a central focal point, symbolic portal and pond, its spherical form putting its classical columns through serpentine contortions, and the bricklayers likewise.

The purchase of Vines House in 2014 enabled the removal of one of the offending carports, thereby reclaiming the Western Terrace. This terrace is supported by a brick wall with a ragstone plinth similar to its Eastern counterpart but without the sloping bank. This wall contains C16th work, evidence of the earlier phase, while the wall behind it, now the Western boundary wall, includes at its south end a real surprise in the return of another section of the brick and flint diapered Tudor wall, again C16th The heavily buttressed rebuilding of this Western boundary wall was necessitated to support the neighbouring carport and is proportioned on the classical orders, with roundels or bull’s-eye openings, some blanked out. The repair of the Tudor work at the south end has so far been obstructed by neighbours. At the north end a yew tree judged to be about 250 years old has been saved within a corbelled brick planting box.

The Northern wall has a red brick plinth, c1700, and has over time been heightened in several phases and types of brick. Our work gives this palimpsest a further phase, adopting the hand made red brick used throughout the Mannerist garden to frame and incorporate this North wall into the Mannerist vocabulary. Closing the garden in at the North, was never intended in the 16th and 17th centuries, and is a result of the division of the garden when Vines House was built, c1694.

Because this wall did not exist in the Tudor or Mannerist phases, arches have been pierced through its central section to allow views through from both sides without compromising the individual identities of the gardens that have since evolved. Curiously the wall here already had arches under the plinth. The new arches above the old have opened up a new axis north- south, from the heart of the Parterre, to the throat of the Chalice, populated by statues.

All the walls and staircases are built off surviving walls or footings, some of the fragments hardly more than a few bricks. Looking closely at the rebuilt work will often reveal the informing fragments and surviving sections, the stem cells from which the new work grew. At the opposite pole to this literal or reinforced repair and reconstruction are our innovations, which accorded with the spirit of Mannerism. Thus the Chalice with its spherical form putting its classical cut brick columns through serpentine contortions, and most ambitiously in the construction of the Gazebo.

This complex little building has a cylindrical brick chamber or core, and an oculus open to the sky within a brick dome. This dome, mostly hidden from the outside is nevertheless the defining feature of the gazebo. With its oculus, we are linked straight to the Pantheon -Rome’s most complete survival from antiquity. Once inside the stately portal a strange world unfolds –the dripping stalagmite in a silvery slit of light, the stone step-ends Built on the most prominent and exposed corner of the garden, the Gazebo is an extension of the three walls it conjoins. Only on the west elevation, where the parapet is lowered is the dome visible. Part fortified gatehouse, part decorative pavilion, part grotto, part stair tower, part banqueting house, this self conscious antiquarian conceit is based on a circle within a rectangle. The iron windows and proposed railings to the High Terrace are as if additions of the C18th while its squint windows are not mere antiquarianisms but light the radial flight of stone stairs. One to cardinal south, allows the sunlight to strike through the overhead drum and illuminate the mysterious brick heart. The building’s core function is to link the intermediate and upper terraces of the garden, the stone steps winding their way around this core to the High Terrace.

At the time of writing we have managed to rebuild about one third of this High Terrace which originally extended widely to the west, picking up with the flight of stone steps which were excavated with the removal of the first carport on the Western Terrace. This flight of steps reveals evidence of the two early phases, the Tudor wall being punched through by the stone steps, to provide access to the High Terrace, thus creating the Renaissance form. This flight of stone steps (C.1630) has flint and brick cheeks to conform with the parent Tudor wall. Here too lies the return of the Tudor wall on the Western boundary. Upper sections of this wall were evidently destroyed when the carport drive was built, telltale knapped flints still adhering to the concrete footing of the yellow brick dwarf wall that ignominiously buried it. Incredulously these neighbours dispute the importance of the wall and its listed status, claiming their carport has precedence. Heritage? Not in My Back Yard.

Beyond our boundaries

Saving the remaining parts of the garden, beyond our boundaries and in unsympathetic ownership will be the challenge for the future. For the moment we can concentrate on all those parts in our control. The four enclosing walls now substantially accomplished, the design of the central plat becomes paramount.

The Oculus lit dome.

Building the Gazebo with top of vaulted entrance to cylindrical core.

The series of arches support the dome.

The dome which is built of specially shaped half bricks.

RENNAISSANCE WATER GARDEN

Given that the garden was built beneath a natural spring the possibility of lavish water display seems very likely. Unfortunately no evidence of how the water was used has yet come to light but given that the spring later became a reservoir the use of a head of water and gravity feed is most likely and is the method which has been incorporated. A large Tank Room has now been created behind the rebuilt section of the Tudor wall. This feeds the various water features including four ponds, the water canons and water railings. The water itself is sourced from the original aquifer, by means of a borehole, already in operation and adjacent to the tank room, and re circulated after cleaning.

No evidence of the planting of the garden survives but the presence of parterres worked into the design is most likely. Our proposed design coincides with the discovery of a hitherto unknown drawing of a closely related garden at Bridge Place, near Canterbury.

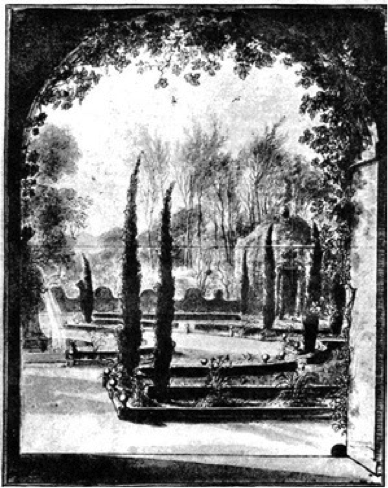

This drawing by Willem Schellinks was done in 1661 when he stayed at Bridge Place, his host Sir Arnold Braems, was a Royalist MP and almost certainly knew Sir Francis Clerke, who inherited Restoration House from his father in 1652, and was also a Royalist MP. Schellinks describes Bridge Place as a sort of paradise ‘with its own deer-park stocked with hart and hind, woodland, a rabbit conservatory, very fine and skillfully made pleasure-gardens and orchards which are all irrigated with an ever running, fresh, crystalline stream of wonderfully sweet water’. The pleasure gardens he drew show a plan strikingly similar to that we had already arrived at. The circular pond like our Chalice, likewise with splashing statue, sends out semi circular waves of path and parterre, theoretically striking the boundary walls and returning on itself, the thus enclosed wing shapes edged with low hedging, accessed through openings in the hedges. All this corresponds closely with our independently arrived at design. The garden is enclosed on one side with yew hedging cut high into Dutch gables, and a spiral columned Yew House forms a corner pavilion approximately where our yew tree survives, prompting us to plant a corresponding yew hedge, destined to be cut into high Dutch gables.

Water garden plan

The high level of coincidence between our plan and Schellinks’ drawing lent authority to a process which had hitherto been the product of inspiration, whereas this was a meeting of imaginations over time.

Schellinks view

Schellinks view was framed as if seen from an arched colonnade chimes with looking through the arches from the Parterre. The area north, beyond the scope of Schellinks’ drawing, our Palimpsest wall is further characterized by two low brick arches.

Asymmetric to the plan they most likely date from the division of the garden C1700, when the reservoir was built and the water piped (in dug out elm pipes) to Rochester and sold. Alternately open conduits flowed under these arches and down to Eastgate where there was evidence of communal drinking troughs and water utility until relatively recently. At any rate, here in the ragstone plinth of the North wall are examples of water management and they became, by their very Rusticity a catalyst for another style. By now the variety of styles brought fears of architectural promiscuity but during the many years of building and thinking about the garden a whole range of influences and references came to bear, the skill lying perhaps in making all the pieces fit and seem natural.

Here gothick pointed prow planting boxes flank a watery island where the statue of the Centurion stands, his head cocked towards Inigo Jones, whose own gaze is directed south east, to Hercules, and beyond that to Italy itself.

Obviously the original context of the garden has been greatly altered since the 17th century when not only river views but surrounding countryside would have given wonderful ‘prospects’ and borrowed scenery. Between the new garden and the Brewery and to compensate a little for this loss, we are planting an orchard of fruit trees, most likely strong on cherries to invoke something of Samuel Pepys’ reference of 1667 to ‘the cherry garden’. A Vinery, and a vegetable gardens will be planted against the south facing wall. An access tunnel with pilasters topped with brick obelisks will complete the East elevation and will link the formal garden with the orchard.

The principal materials of the garden were red brick, flint and ragstone. The staircases appear to have been built in brick, probably because of the intractable nature of local ragstone, then partly overbuilt in more enduring stone. We have opted for stone treads, re used igneous grey, which visually ties in with the grey flint though not local.

The statues play a special part in the garden, alluding at once to the Italian tradition with the bust of Inigo Jones presiding from the Western wall, his gaze coincidentally inclined towards Italy. The bust is English, and based on the Van Dyke portrait in the Hermitage, but probably dates from the C18th when Jones was a continuing architectural influence and something of a cult figure.

The statue of the Centurion has a link to Jones, strongly resembling his drawing for

the costume of Oberon (1611), which shows a similarly Roman clad and helmeted soldier. Our statue carved from Barnack stone probably dates to the early C.17th and represents not Oberon but Castor with the iconography of the water loving beaver at his feet. Beavers were admired for their building skills.

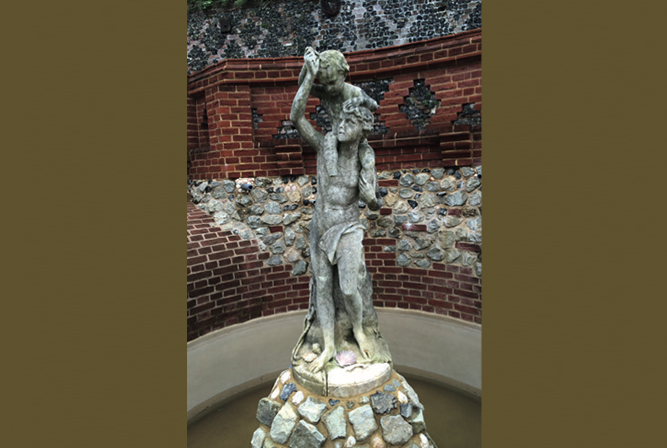

The statue in the Chalice of a younger boy being carried over water by an older youth may take its inspiration from St Christopher, the subject and sculptor as yet unidentified. Above on the High Terrace, the figure of Hercules is by contemporary British artist Matthew Darbyshire. The original of this was made in polystyrene and featured in the

2015 Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition ‘Following Hercules’ while this outdoor version is otherwise identical but made in weatherproof plaster. This figure represents the herculean tasks we set ourselves in recovering and re creating the Tudor wall and Renaissance water garden.

The Oculus dome.

The Chalice with unidentified marble statue

The gazebo from the gate piers

The west face of the gazebo from the rebuilt Tudor Wall